What To Do About

Spotify

Re-imagining the streaming economy

Everyone thinks they know how to fix the streaming economy. A lot of people think it's as simple as cancelling a Spotify subscription, or removing your music from the platform. Well, it's my view that these "solutions" are barking up the wrong tree. So the goal here is to define the right tree up which to bark.

This is an essay about fixing the streaming economy. On its face, it will probably make a lot of people mad. (What doesn't these days?) But I think building a healthy streaming economy means completely rethinking what it should be & how artists should be compensated.

There is no solution for all 12m artists to be fairly compensated with the current system. Well, technically there is... it's called socialism. But that's outside the scope of this essay. To fix things, I believe we have to think within the bounds of capitalism & think creatively.

Here's an outline of my ideas...

- Major artists are paid way too much

- Record labels have far too much power over streaming platforms

- Mid-tier artists aren't paid nearly enough

- The lack of mid-tier artist compensation destroys the real music economy... recording studios, recording professionals, touring, touring professionals, local instrument shops, etc.

- Artists with low-volume streams should be looking to the real music economy & high-margin transactions (physical sales, subscription clubs, etc.) for compensation, not streaming.

- There is no market solution to the streaming economy's problems, they must be legislated.

- A progressive payout model that funnels revenue to mid-tier artists, administered by a non-profit, gov't-funded agency will do more to create a health music industry than anything I've seen suggested.

Let's start with regulation

The core of Rashida Tlaib's Living Wages For Music Act was the proposal of an independent, non-profit organization to oversee streaming payouts, similar to how SoundExchange oversees satellite & digital radio royalties. And this seems like the fundamental component to fixing the worst problems with the streaming economy. This arrangement would make it impossible for artists & labels to negotiate catalog licensing fees, minimum payment guarantees, or other sweetheart concessions that come at the expense of independent artists, correcting a system that has been lop-sided in favor of the major labels from day one. A third party overseer of payouts guarantees that no artist is treated more favorably than another & ends the debate about which streaming service treats artists more fairly.

Legislation that sets up this type of organization could also require that artists confirm that they own the copyright to any song they upload, discouraging the collection of royalties via AI prompt songs under penalty of law.

But even more can be done to even the playing field. Spotify's Perfect Fit Content program should be outlawed on the basis that it's anti-competitive. A well-performing song on an editorial playlist shouldn't run the risk of being replaced by an imitation song in the PFC program. And labels should be required to divest from their playlisting companies, or at the very least disclose when playlists are not un-biased curation, but label marketing. This would follow the requirement that YouTubers & social media influencers disclose when the content they create is sponsored.

Streaming services like Spotify should also be required to engage with independent artists directly, rather than forcing them to go through third party distributors. These third party middle men increase administration costs & make it difficult for independent artists to rectify disputes with Spotify over things like stolen music, terms of service violations, or profile errors. This is Spotify offloading the cost of administration to the artist, who have to pay subscription or listing fees to these third party distributors. Companies like DistroKid, TuneCore, CD Baby, & AWAL shouldn't exist.

The progressive payout model is progress

But few things would address the common complaints about the streaming economy as much as adopting a progressive streaming model, which values streams less as they accumulate.

Taylor Swift was streamed 2.21b times per month last year, which is about $8.8m per month at the standard $0.004 calculation. We can't know for sure if she has a guaranteed rate that's higher. But it's tough to make the argument that she's "earning" that $105m per year. Because the funny thing about capitalist society is that once you reach a certain level of exposure, you turn into an exposure magnet. ESPN sends push notifications to every football fan that you've become engaged. The Atlantic calls it "breaking news." Capital One wants you to hawk their credit cards. And questions begin to surface like, is she really the Time Magazine Person of the Year, or was she simply the choice that would sell the most magazines? Can the decision be both meritocratic & opportunistic? Maybe, but only if you define the ability to sell things as the highest form of significance. Which, to be fair, many do.

But I don't. I don't think that she's putting in 100x more work or is 100x more talented than someone who is receiving only 22.1 million plays per month, which is itself nothing to shake a stick at. Therefore, I think it only makes sense to pay out less as plays accumulate.

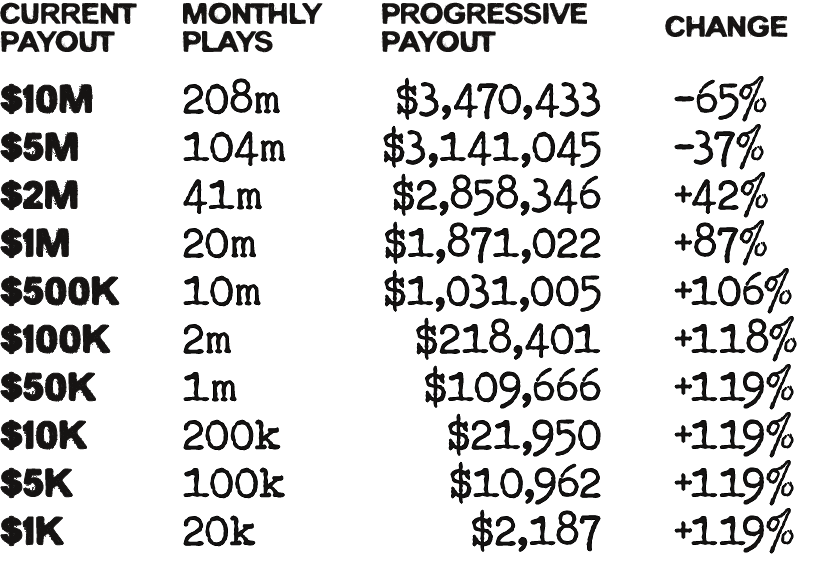

A progressive payout model can be shaped in various ways. The severity & duration of the curve can be adjusted. The amount of plays paid out at the base rate (before the curve kicks in) can be adjusted. The algorithm can take the value of a play all the way down to $0.00, or a minimum payout floor can be enforced. And all of these variables shape the outcome of the model. You can even enforce a minimum play qualification for receiving payouts. (More on that later.)

The particular algorithm I'm using for this essay pays out at the base value for an artist's first 500,000 plays, then decreases in value over the next 4,500,000 plays, bottoming out at 3% of the base value, then all plays thereafter are paid out at that 3% of base value rate. The base play value is $0.0087, which came from using Spotify's Loud & Clear Report to approximate the total number of plays for all artists who generated $1,000 or more in 2024, offset by the algorithm & divided into the $10b Spotify paid out in total royalties. (This calculated tiers at Spotify's listed pay groupings, so anomalies like Taylor Swift were simply counted as $10m in annual payout.)

The result is that for Spotify's 274,000 most-played artists, payouts to 272,550 artists' payouts doubled & payouts for all but 210 increased substantially.

In very basic terms, the way this payout model works is that the value of a play starts out at double the value of the average pro-rata play ($0.0087 vs $0.004). And they decrease in value over time, dipping below $0.004 at around 30m plays. And total payouts become less after around 120m plays. This may seem like a very high amount, but consider that this is less than 20% of Taylor Swift's 2.21b monthly plays.

The calculator below illustrates how different monthly play counts pay out, but this more robust calculator will allow you to explore the ins & outs of how the model works & where the data comes from. And this Google Sheets doc shows exactly how the algorithm applies to Spotify's different pay tiers.

But why disqualify artists who make less than $1k per year from payouts?

This is a good question, which requires a somewhat indirect answer: many artists with relatively low-volume streams can make more by making less. Or, alternatively, concentrated payouts increase the value of a dollar within the real music economy, which finds its way back to individuals working within that real music economy.

The artists who are disqualified from payouts here are receiving checks of $83 or less per month, oftentimes much less. And that money may go toward a few meals or gas or some other necessity... something outside of the real music economy. But if that money is used to double the streaming earnings of mid-tier artists, these new payouts are more likely to go towards recording sessions, music gear, merch, or additional touring. This means more opportunities for niche or young bands (more, better opening tour slots, better indie label advances, etc.), & also new opportunities for music employment that might boost the career of an artist.

The velocity of money within the music economy, in other words, can be more valuable to these artists than the small checks for low-volume plays.

Re-imagining the record label

The major record labels have used their dominant presence on streaming services like Spotify to re-introduce gatekeeping to the industry. Their usefulness is to make it harder for independent artists to build an audience & get paid, & easier if you simply go through the label. You'll be automatically added to popular playlists, given priority within the recommendation algorithm out of the gate, & you'll benefit from the label's guaranteed minimum per-stream payouts. And yet, they're not providing the recording budgets or artist development services that labels once provided. This Rick Beato video, where he critiques Warner Music UK president Joe Kentish's comments, is a bit hyperbolic but also not entirely off base. Whereas Sony CEO Doug Morris originally climbed the latter in the industry not by finding & developing artists, but by scouring regional sales reports for artists finding success on their own, the entire industry has pivoted toward relying on social media metrics for discovering & signing artists. The responsibility for finding success now rests largely on the artist & their ability to chart their own path, & then the label swoops in & opens the door to new levels of exposure & wealth, taking the lion's share in the process. This is why Kentish is placing so much emphasis on "productivity" & "the ability to communicate to an audience," rather than artistic perspective or musical talent.

But if we can create an industry that levels the playing field, the ability for the labels to enforce royalty rates as low as 20% disappears. I believe we should legislate a minimum royalty rate of 50%, & require that artists currently signed to these absurd rates be allowed to renegotiate.

But we don't need to stop at fixing the payout model, the Spotify platform itself needs some changes.

Acknowledging the humans

Spotify has improved the UI in recent years, adding the ability for artists & labels to list producer & songwriter credits. But there's no reason they shouldn't allow for all recording credits, & allow for those credits to be searchable. Spotify currently allows for search modifiers like label:"light in the attic" or year:1982 or genre:"power pop", but does not allow searching on current credits, like producer:"Denny Cordell". If that were supported & credits were expanded, searches like organ:"Garth Hudson" could bring a musician's varied discography to life, creating new avenues for discovery outside of the sameness of the algorithm.

Empowering human discovery

The recent move to re-introduce messaging to the platform is a positive step. But Spotify must also do a better job of exposing playlists to users that aren't based on moods or niches, but instead on taste, optimizing for surprise, rather than passive engagement. There's a place for those playlists, there is more than one mode of listening.

Putting a bow on it

I believe these changes could transform the music industry without being particularly disruptive. And I think they're doable, because there are far more artists who desperately need an overhaul of the industry than there are individuals who benefit from the lopsided system that exists, & I believe in the power of democratic movements to bring about change, even in a post-Citizens United world. We just all need to be barking up the right tree.

Who the fuck is Jon W Cole?

.jpg)

To be honest, I probably shouldn't be the one writing these essays. It's just that no one else is. And it feels like someone probably should.

I'm not a journalist. I'm not an artist. I don't work in the music or streaming industries. I'm just a web developer. But I have a lot of friends who are artists. And so I know what the struggles are. And when I see the discourse online, none of it really seems to be pointing toward any real solutions that are going to make a better industry for my friends.

These essays are meant, first & foremost, to start constructive debates. And I would love to hear thoughts from folks who are more deeply plugged into the industry than I am. I certainly have blind spots. And I intend to update these essays over time based on feedback.

At me on Threads @jonwcole, or e-mail me at jon@jonwcole.com.

Cheers.