What To Do About

Spotify

The Great Unbundling

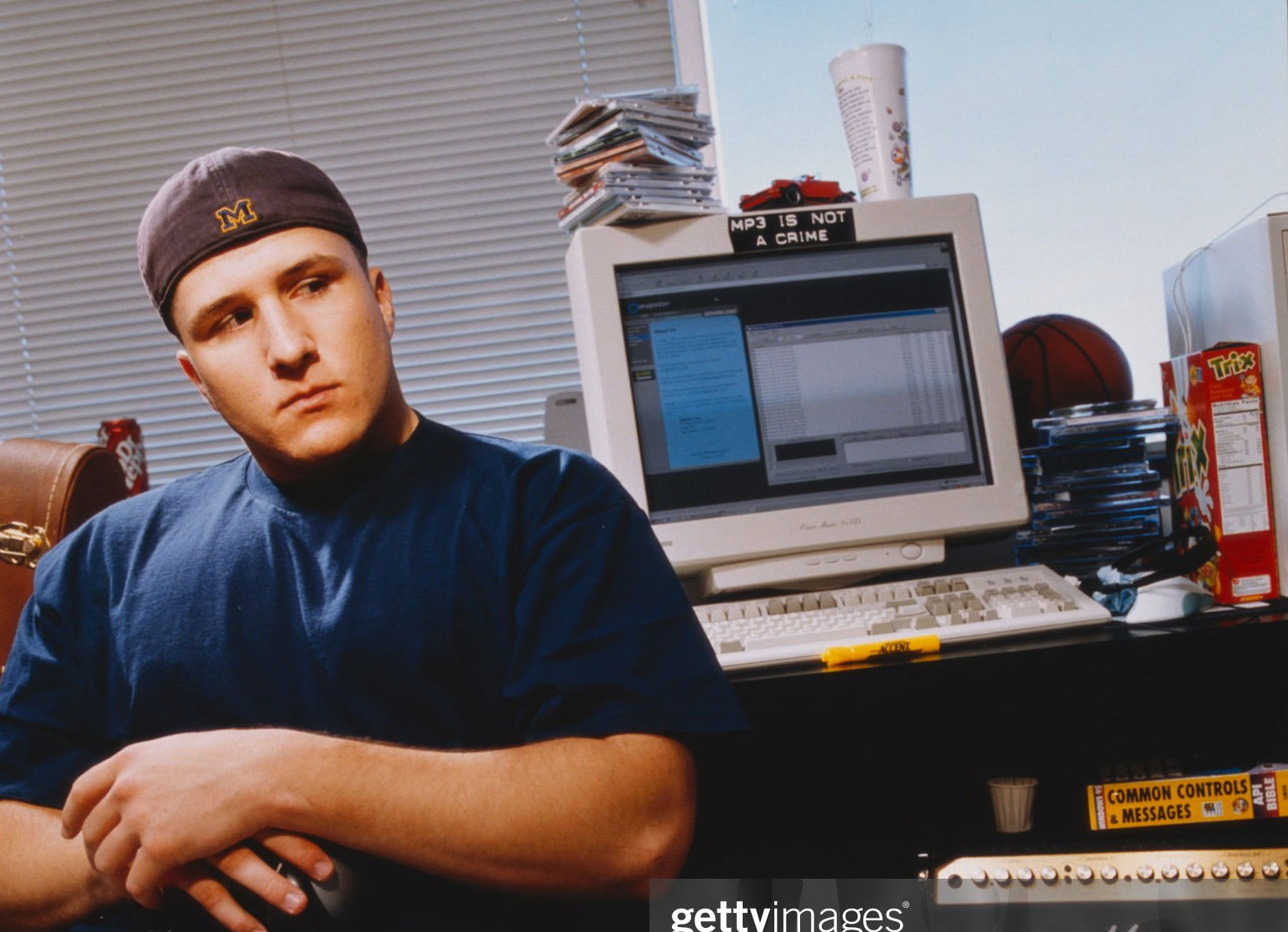

We've all heard the story about how Napster ushered in the piracy era & nearly caused the recorded music industry to implode during the aughts. But what if that's not true? What if the story of the industry implosion during the 2000s was actually the story of the iPod, the legal digital download, & the unbundling of music? Could it be that we all believed a lie?

To really understand what the internet age hath wrought upon the music industry, we have to first go back (briefly) to the days of vinyl album format. This was when 8 of the 10 best-selling records of all-time were released. Thriller, Back In Black, Dark Side of the Moon, Hotel California. Ask any boomer & they will tell you this is the case because music was better & more meaningful back then. But in truth this is just a story of timing & format evolution. All of these albums were purchased by their fans on vinyl. Then again on cassette tape, maybe even 8-track. And again on compact disc. And perhaps also as digital downloads. And now they're regularly streamed. The albums that maintained popularity through this era of rapid format turnover will forever remain the top 10 best-selling records. And it's true that we adopt new formats in pursuit of convenience. But the music industry will always jump at the chance to sell you the same music a second or third or fourth time. It's the easiest money they make.

By the 1990s, everyone was so high on the hog that a sense of entitlement had begun to set in. There were still great albums being recorded, but there was also a one-hit-wonder phenomenon taking root, exacerbated by the growing corporatization of radio. The industry began to lose a sense of obligation to music fans to put out whole albums that were great, simply moving forward if they found a song they thought would perform well on radio. The stories of disappointment from this era are legion.

If you wanted to own Meredith Brooks' provocative radio smash Bitch you'd also have to purchase eleven songs that are "considerably calmer and aimed at adult alternative stations." If you'd like the Primitive Radio Gods' Standing Outside a Broken Phonebooth with Money in My Hand, you'd be let down to learn that "there is precious little on the album to hold the interest of anyone drawn in by the lead single." If you wanted Chumbawumba's pub anthem Tubthumping, you'd learn that "there isn't anything quite as good on the remainder of [the] album." In other words, consumers were no longer paying $15 for 15 great songs. They were paying $15 for a single song, & they were just getting 14 additional songs they weren't particularly interested in. And it wasn't that mediocre albums were anything new. But this was the first time singles from mediocre albums were being marketed incessantly on standardized playlists in every market thanks to radio industry consolidation at the hands of corporations like Clear Channel (now IHeartRadio) & Cumulous.

The one-hit-wonder phenomenon bubble could've been avoided if the industry sold CD singles like they did during the singles era of the 1950s. But instead they continued to push the album format despite the declining value of album content. And so the product became overvalued by as much as 90% on an album-to-album basis.

This built up consumer resentment that served to justify the adoption of piracy, but piracy was itself not a wholesale replacement for legal purchases. Studies suggested, in fact, that the users who pirated the most also spent the most on music because they were the biggest fans. And much of piracy was simply an act of benign opportunism.

If I could freely duplicate helicopters, for instance, I might duplicate 100 helicopters in my backyard. But that doesn't mean that I ever could have or would have purchased a single helicopter, nevermind stolen one from another person. The phrase "theft," which the industry loved to use to describe piracy, obscures what was really happening. The amount of piracy that actually impacted revenue, in other words, was vastly overblown. There was an opportunity for piracy & bundled music (which is to say the CD economy) to co-exist. But the industry adopted legal downloads instead. And that is where the fatal mistake was made.

The industry was oblivious to the growing resentment among consumers toward the industry in response to the one-hit-wonder phenomenon. They were blinded by the massive success of artists like N*Sync, who had just sold 2.4 million copies of their No Strings Attached record in just the first week. So when they agreed to license their catalog to Apple's iTunes store (after numerous attempts at starting their own digital stores failed in comedic fashion), they assumed that sales would translate directly, which is to say that people would buy whole albums. And if they didn't, that at least they would get a sales bump from people buying Thriller, Back In Black, Dark Side of the Moon, & Hotel California again for the fourth time. But it turned out that people only wanted to buy the single. And people who already owned those CDs could simply copy them to their computer.

An optimistic onlooker might think that an iTunes user might simply buy 15 singles by 15 different artists in place of the album cuts they were passing up. But it turns out it's far more expensive & difficult to develop 15 artists with marketable singles than it is to simply force consumers to buy the album cuts. That's why the industry hadn't already adopted CD singles to any meaningful degree.

The industry framed this as a pirate attack. But really it was a bubble burst. Every legal consumer that switched from CDs to digital downloads spent about $14 less per purchase. And Steve Jobs was putting millions of dollars behind an iPod marketing campaign that was supercharging a paradigm shift that was sure to bring the music industry to its knees.

In a now infamous Wired Magazine profile, then-Universal CEO (and current Sony CEO) Doug Morris revealed how comically unprepared the industry was for the digital era. "That's a misconception writers make all the time," he said, "that the record industry missed this. They didn't. They just didn't know what to do. It's like if you were suddenly asked to operate on your dog to remove his kidney. What would you do?... We didn't know who to hire. I wouldn't be able to recognize a good technology person--anyone with a good bullshit story would have gotten past me." Even if the industry leaders now realize the role that Apple played in the collapse, they're unlikely to let on because they'd rather play piracy victim than to own up to their role in creating & bursting the bubble.

But the story is in the data.

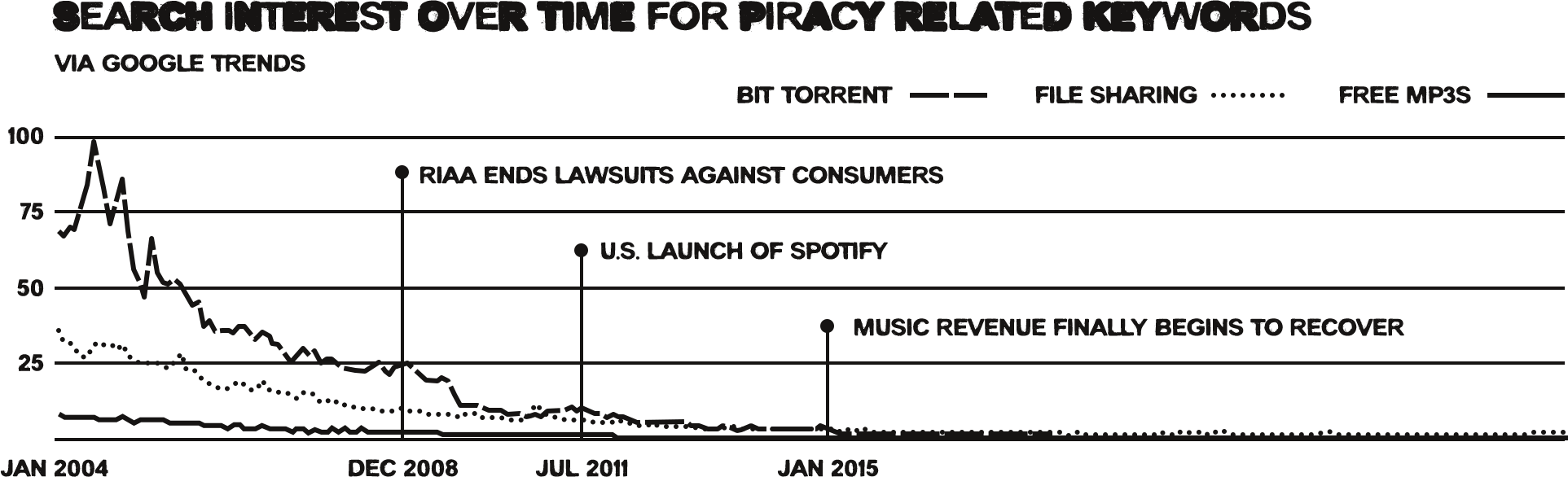

The fight against piracy, quixotic as it was, had its successes. They shut down piracy services like Napster, Limewire, & Kazaa with lawsuits. They shut down private bit torrent trackers like What.CD & Oink's Pink Palace with governmental raids. They forced Google to filter links out of its search results that pointed to pirated content. By late 2008 the RIAA came to terms with the the overriding fact that no victory against piracy was going to stop the decline of revenue, & they wisely abandoned the war against consumers entirely. This was portrayed by the media as a victory for pirates, but the truth is that the industry had largely won its war against piracy at this point. It just hadn't gained them anything. The availability of & interest in pirated music had declined precipitously, but the industry collapse would continue for another 5 years.

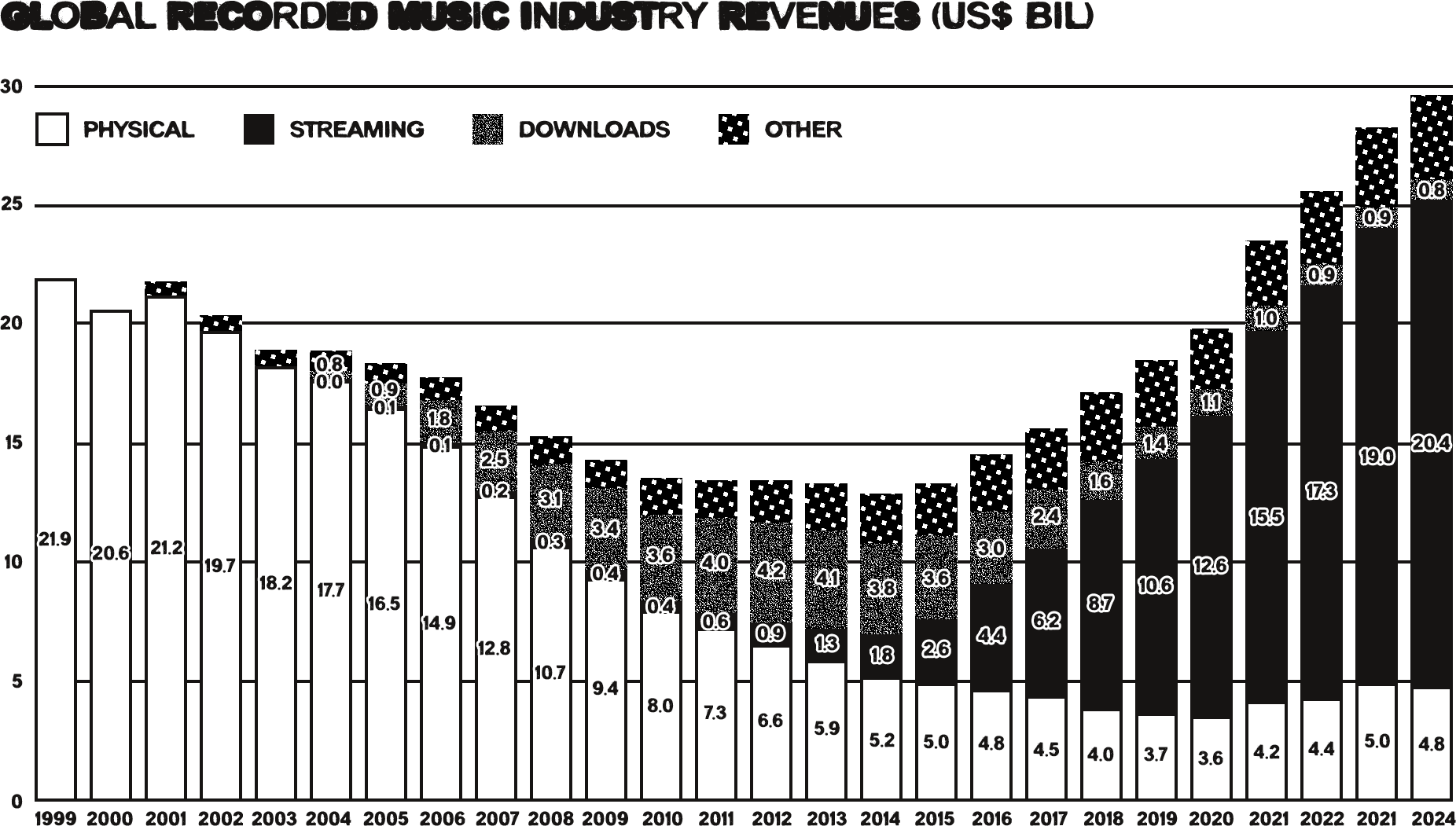

The correlation between piracy & the decline in revenue doesn't seem to exist. So there must be something else behind it, and there were plenty of suspects. The decline of mTV, print media, & terrestrial radio eliminated traditional marketing channels for new music. The war against consumers had eliminated all of the industry's good will. The rising blogosphere championed music that clashed with the taste of major labels. And yet, one suspect stands above all the rest: throughout the decline, legal digital downloads were cannibalizing physical sales. The correlation is clear. It's no coincidence that the peak of digital downloads represented the trough of global music revenue. And this only changed when monthly streaming revenue began to replace the revenue lost from the abandonment of bundled music. And not only does overall revenue grow as the digital download format is abandoned, even physical sales revenue eventually increased for the first time in two decades.

Spotify is oftentimes credited for providing a better alternative to piracy. But far more importantly, Spotify offered a better alternative to digital downloads & a reason to pay $10 per month as opposed to $1.29 every so often for a single song. This was so true that even Apple--the key driver of digital download sales--abandoned its iTunes music store & pivoted to Apple Music streaming.

And yet the broader sense is that--despite the obvious recovery--it's harder than ever for artists to earn a living. And while there may be truth to that, solutions won't be found in simply scapegoating the streaming format or Spotify specifically.

Who the fuck is Jon W Cole?

.jpg)

To be honest, I probably shouldn't be the one writing these essays. It's just that no one else is. And it feels like someone probably should.

I'm not a journalist. I'm not an artist. I don't work in the music or streaming industries. I'm just a web developer. But I have a lot of friends who are artists. And so I know what the struggles are. And when I see the discourse online, none of it really seems to be pointing toward any real solutions that are going to make a better industry for my friends.

These essays are meant, first & foremost, to start constructive debates. And I would love to hear thoughts from folks who are more deeply plugged into the industry than I am. I certainly have blind spots. And I intend to update these essays over time based on feedback.

At me on Threads @jonwcole, or e-mail me at jon@jonwcole.com.

Cheers.