What To Do About

Spotify

Then and Now

If you ask a child what they want to do with their life, chances are that they want to be a YouTuber. Survey after survey shows that YouTuber/vlogger/blogger is by far the most appealing career, & that they relate to YouTubers more than traditional celebrities. It seems so attainable... anyone can buy a ring light & start uploading videos from their bedroom. (Guchi!) And yet... it's not. An entire industry exists to sell ring lights, condenser microphones, neon mood lighting, & teleprompters to aspiring vloggers who may never receive more than a few hundred views, if that. There is no end to the number of YouTube gurus offering advice on how to grow your channel. But building an audience is difficult, & even those who manage to do it often times quit (or scale their channel back) because the demands of producing content to please the algorithm sucks much of the joy out of it.

None of this stops the kids from dreaming, though.

I guess it's a great job if you can get it. But as the Scots say, "the best laid plans of mice and men often go astray." And many more ring lights will be sold to dreamers than used on monetized YouTube channels.

It's hard not to see parallels to the music industry here. A music career seems so attainable... buy an audio interface & a mic, google "how to record guitars," upload your track to Spotify, record a music video on your phone... it's all possible. And there's even a chance that you'll become a viral sensation, like Jesse Welles. Maybe you're just a couple of clever Instagram reels away from performing on a late night talk show or at Newport Folk Festival. It's gotta happen for someone, right? Might as well be you. I'm not here to tell you it can't. I'm not here to tell you no. I'm not here to stop you from pursuing your dreams.

But there was a time when people's whole jobs were to do just that. To tell you no. A&R guys. Radio program directors. They were the gatekeepers, deciding who does & doesn't have the ambiguous "it." Want your music available for purchase in stores? Gotta impress a gatekeeper first. Want your music on the radio? Gotta impress a gatekeeper. Want a feature in Rolling Stone magazine? Gotta impress one o' them gatekeepers. This was the era of "big breaks," presided over by "big wigs" who shaped culture from their LA or Manhattan offices. It was a real bummer time... unless you made it through the gates.

During this period, which lasted from the '70s to the early aughts, there was a major distinction between the nobodies & the somebodies. The industry was set up such that so few people were allowed in that there was plenty of money to go around. You could sign a predatory record deal because there was so much money on the table that a hit might make you tremendously wealthy even despite the criminal contract terms. (Though not nearly as wealthy as the label executives.) And if your record flopped, the record label was skimming so much money from successful artists that they might give you another six figure advance just to try again. Even indie labels were regularly handing out tens of thousands of dollars to unproven artists.

On a given week in 1999, you might see 100 or so new releases in CMJ Magazine. And that was, for all intents and purposes, the entire industry. Your local Best Buy or indie record shop might receive some small fraction of that for their New Release section, catered to their clientele. But it was genuinely possible to keep up with all the relevant releases. It wasn't particularly unusual to be familiar with most if not all of a given year's Billboard 200 chart because the industry was so tightly gatekept.

But those days are long gone. With upwards of 20,000 songs being uploaded to Spotify every day, we're seeing as many releases every few days as we'd see in an entire year during the CD era. Precisely because there's no one telling artists "no."

And in some ways, that's great. Artists who might've been told "no" in the '90s can forge their own path & make a living doing it. There are hundreds if not thousands of artists living this dream, playing the role of the label themselves, retaining ownership of their recordings, & making a comfortable living off of it. Maybe not exclusively off of streaming revenue, but they're making it work.

It's a nice job if you can get it.

But there's drawbacks to the end of gatekeeping, too. For every artist who has found an audience & made it work, there are thousands more struggling to cultivate a fanbase. Well, some are struggling. Others just upload the songs & expect the fans to find them. Then they complain about it. The degree of effort actually being put in varies wildly. But the point is, there's never been a time in history when there was more competition for 4 minutes of attention. Or for a slice of that monthly subscription fee.

The dichotomy here is pretty clear: gatekeeping meant severe limits on artistic expression, but better compensation. The end of gatekeeping means limitless artistic expression, but not enough revenue to go around. Clearly, neither of these outcomes are optimal.

Unfortunately, compensating artists better isn't something we can simply decide to do. Even if Spotify hypothetically cut it's take from 30% to 15%, at 15% bump in royalties isn't going to resolve most artist's compensation complaints. If Daniel Ek sold his ownership shares & donated the proceeds to artists, that would be a one-time payment & a nice Christmas bonus but still wouldn't solve the long term problem. Raising the monthly cost of subscriptions would just lead to subscriber attrition & lower overall revenue (encouraging users to downgrade to the free tear or return to piracy). And onboarding new subscribers... well, that's already Spotify's primary goal.

I think finding the optimal solution here--the right compromise--begins with imagining what an ideal music industry might look like.

The state of the union

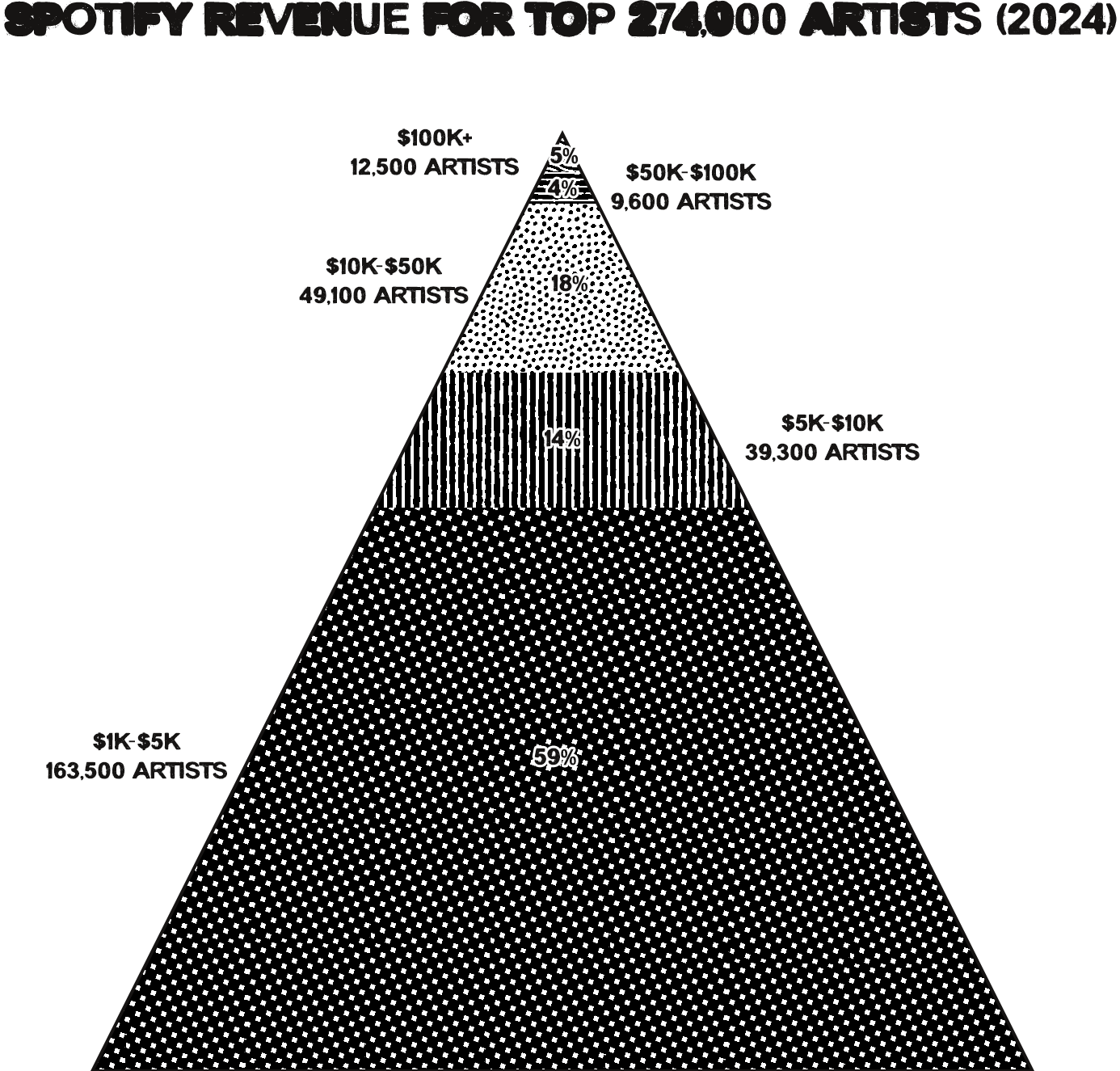

According to Spotify's Loud & Clear report, 12,500 artists generated $100k or more in Spotify royalties in 2024. That sounds good, but if the artist in question is a 5-piece band with a manager who are signed to a record label, $100k doesn't go as far as you might think. Band members could end up with as little as a couple thousand bucks each at the end of the year.

Of course, if they're independent & own their recordings, that $100k looks more like fifteen grand per band member. But if that's the case, it's far less likely that you're generating that much revenue. It's far more likely that you're one of the 12 million artists who aren't.

So if we can choose to reimagine the industry however we want, my interest is in paying as many artists the equivalent of a minimum wage salary through streaming as possible. That means $15,000 per band member. And if we work backward for a 5-piece band at a 20% royalty rate, that requires about $500,000 in Spotify earnings, which is the rarified air of the top 3,000 artists. I'd like to see that number grow to at least 50,000. That is what I believe would be thriving professional class of musicians.

To get there, I think we need to redistribute revenue from the top & the bottom toward the middle.

A little off the top...

In 2024, 1,450 artists generated more than $1m in Spotify revenue. And 70 generated more than $10m. The exact numbers aren't available, but this top 0.01% of Spotify's 12 million total artists accounted for at least a third of Spotify's $10b in payouts, likely much more.

This type of concentration is accomplished in part by sweetheart deals that artists & labels negotiate with Spotify. A superstar like Taylor Swift threatens to pull her music off of the platform if she's not paid more, so she negotiates a guaranteed minimum per-stream payment that may be larger than the pro-rata value of her plays, making her slice of the revenue larger at the expense of everyone else. We don't have much insight into exactly how artists like Swift or Led Zeppelin or Thom Yorke were wooed back onto the platform, but we do have some of the original label agreements with the service, like this Sony/Spotify contract, which featured a litany of compensation perks that came at the expense of independent artists.

During the CD-era, things worked the opposite way as they do now. If someone bought a Taylor Swift CD, no matter how many times they listened to the album, Taylor & her label would only get that $15. If you bought your sister's boyfriend's punk rock CD & only listened to it once, he, too would receive $15. Street urchin or sequined superstar, those shiny little discs cost the same.

In the streaming era, though, the math changes. Your sisters' boyfriend would generate just $0.05 for 12 streams. And Taylor Swift, if she's paid out at a preferred rate calculation of $0.006 per stream, rather than the standard $0.003-$0.005, would generate $15 after about 200 streams of the album. And even more in perpetuity.

The labels figured out early on that if they can't gatekeep at the distribution level, they can still use the leverage of threatening to withhold their catalogs to gatekeep at the payout level.

The current system rewards artists who are given a launchpad to success & penalizes artists starting from scratch. But it doesn't have to be this way.

For instance, our progressive federal tax system was created to tax high earners at higher rates than low earners, recognizing that participation in society should be contributive & not extractive, & that prosperity should be shared and not hoarded. And its implementation lead to the birth of the American middle class & the largest expansion of wealth in world history. We could do the same thing for artists with a progressive approach to streaming payouts.

This system would divide play counts into brackets, & higher brackets (like plays over 1m during a given pay period) would pay out at a lower rate than lower brackets (like the first 100,000 plays). This type of system would reduce inequality within the streaming economy (redistributing wealth down toward the middle) & increase payouts to mid-tier, working artists.

And while major artists may take a pay cut, we all benefit from a thriving creative economy. Because more working musicians means more producers & engineers, more recording studios, more instrument shops & better live shows. Perhaps a number of superstars might eagerly trade some portion of personal wealth for a creative renaissance, the type we saw in the 1960s.

High-volume vs high-margin artists

But it takes more than just redistributing from the top. To create a thriving professional class of musicians, we also need to redistribute wealth upward toward the middle from the bottom. It would be great if the streaming economy could support 12m artists, but it can't. And optimizing for an impossibility only leads to a broken system. If we instead strive to create a streaming economy where Spotify can pay the equivalent of a minimum wage salary to 50,000 artists, this means making a distinction between artists who should be optimizing for volume (streaming) & artists who should be optimizing for margins (digital downloads, vinyl sales, merch sales, etc).

There is a class of musicians, either because they're just getting started or because they're making music in a niche space, that won't significantly profit from streaming no matter what changes are made to the streaming economy (even through a user-centric or progressive model). And for those artists, communities like Bandcamp, Vinyl Me, Please, & Patreon are essential to their success. Streaming may work as a promotional tool for these artists, but a sustained career for them comes through high margin transactions with fewer, more dedicated fans.

These artists don't live or die based on odd checks for $5, $10, or $15 dollars. And therefore, in the spirit of optimization, it makes far more sense to--rather than diluting streaming revenue by sending out hundreds of thousands of insignificant checks to low-volume artists, create minimum engagement requirements for payout qualification so that the revenue is delivered in more meaningful payments to middle-tier artists. The goal here is not to deny artists payment, but to target it at working artists who will spend the money on studio recording sessions, equipment, funding tours, etc., growing the broader music economy.

Spotify has already started moving in this direction by instituting a 1,000 play per year minimum for payout qualification, which is intended to disincentivize fraudulent plays & eliminates payments that would amount to less than $4 per track. But making meaningful change for middle-tier artists requires more strict qualifications.

YouTube, for instance, requires 3,000 public watch hours (the rough equivalent of 45,000 music streams) within a 12 month period to qualify for ad revenue share. Most platforms that allow un-gatekept content uploads do not qualify users for revenue share by default, if at all. Users aren't paid for tweeting or for uploading photos to Instagram or for publishing blogs. And some music uploaded to Spotify falls into this bucket: neither high-volume, nor high-margin, simply vanity content.

Spotify's 1,000 play requirement will likely redistribute a hundred million or more dollars upward toward the middle tier in its first year. And this is a good start, but more drastic changes are needed.

Who the fuck is Jon W Cole?

.jpg)

To be honest, I probably shouldn't be the one writing these essays. It's just that no one else is. And it feels like someone probably should.

I'm not a journalist. I'm not an artist. I don't work in the music or streaming industries. I'm just a web developer. But I have a lot of friends who are artists. And so I know what the struggles are. And when I see the discourse online, none of it really seems to be pointing toward any real solutions that are going to make a better industry for my friends.

These essays are meant, first & foremost, to start constructive debates. And I would love to hear thoughts from folks who are more deeply plugged into the industry than I am. I certainly have blind spots. And I intend to update these essays over time based on feedback.

At me on Threads @jonwcole, or e-mail me at jon@jonwcole.com.

Cheers.